The first part of this post will illustrate the current design and marketing interrelationship. The second part will be proposing an ideal relationship model that can offer much higher rates of commercial success.

1. Design First, Sell Later

I will try to explain this approach with a purposefully simplified example; assume that you have decided to develop a strategy game, based on your experience/gut sense/preliminary market research/etc about what will sell in the market at that time. From that point on and to the end result, you will have to make many decisions about the game along the design process.

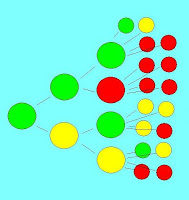

Let's say you want to decide what sort of strategy game it will be: real time or turn based. Based on the results of your decision, you can end up with two completely different games. It is also highly probable that the consumer reaction to (and subsequently the commercial fortunes of) these two outcomes are not quite equal. Green circle in this example represents the better outcome, with yellow being the second best.

Let's say you want to decide what sort of strategy game it will be: real time or turn based. Based on the results of your decision, you can end up with two completely different games. It is also highly probable that the consumer reaction to (and subsequently the commercial fortunes of) these two outcomes are not quite equal. Green circle in this example represents the better outcome, with yellow being the second best.Most game designers pride themselves in understanding the gamers and what they want to play, for they are gamers themselves. I will not argue this point one way or another, at least not in depth, right now. Let us assume instead that in this case the designer has chosen the right option and has decided to go with a realtime strategy title. Everything is perfect for a little while, until you come to the next decision point.

This time you are perhaps trying to decide whether to go with a futuristic setting like Starcraft, or with a medieval theme like Age of Empires. Again one of the two will resonate better with the gamers than the other. Perhaps one of them (shown as a red circle) will be a total flop.

This time you are perhaps trying to decide whether to go with a futuristic setting like Starcraft, or with a medieval theme like Age of Empires. Again one of the two will resonate better with the gamers than the other. Perhaps one of them (shown as a red circle) will be a total flop.Right after that decision comes another: should you include two factions or three? Maybe four? Maybe add customizable factions? As you can see, each decision point adds new combinations and new possible outcomes to the overall picture.

Imagine how many of such decisions you have to make along the design process, big or small, visible or in the background, visual or technical, story-wise or mechanics-wise, and so on. Many decisions later what you end up with is a quantum cloud of possibilities:

Of this huge set of 'alternate universes,' only a small fraction will lead you to a hit title. A greater portion will probably fall under the acceptable or average category, while even greater is the possibility of a complete commercial failure. The aim of the design team is, then, to go through this whole decision tree with the most number of green circles, in order to maximize the chances of ending up in the green zone.

Remember: a green circle represents an outcome that will have the highest positive reaction from the consumers. It is not about chasing an absolute truth in game design. It is about giving people what they will like to play. So the chase for green becomes chasing an insight into the gamers' minds, to find the choices that will resonate with them most.

Guess whose job that is.

If you consult with the marketing people of the big game companies, they will likely tell you about the focus group studies, the open betas, the online forum posts from fans, etc. These things are sure to give you insights about gamers, right?

Let me tell you how well this works: imagine you want to drive your car from Vancouver (BC) to Lima in Peru. If you exclusively relied on the sketchy directions given to you by ten random people in downtown Vancouver, then maybe a hundred more along the way a year later, and not to forget your team of enthusiastic road-trippers, your chances of finding Lima on your own would be about just as high as coming up with a great game that also sells great.

As a consumer myself, I have observed the above scenario many times, with the end result of them ending up somewhere in Quebec instead and spending lots and lots of advertising dollars to convince everyone in town that they are in fact living in Peru. This is known as push marketing.

This is also why they are very unwilling to take chances with new directions. This is why they are more than happy to manage a ballpark with a title (because it is an amazing feat), and then reiterate it countless times with incremental changes, hoping to find the street address one day in the distant future. The problem is, though, the address keeps changing. Thus there is a never-closing gap between where we -as consumers- want them to end up, and what they can manage with their current pathfinding techniques.

2. Concurrent Design and Marketing

The solution: integrate the end user into the design process as much as possible. The best example of this approach is my favorite indie game Mount&Blade, but it is possible to see other examples in many other industries. What amazes me is the fact that the designers of that game got it right in their first try, while most industry people are not even aware of this unbelievable feat yet.

What they did right was releasing the game as soon as it was playable, and continuing the design process along with the end users. Every update got immediate feedback. The reactions to every little change, tweak, fine-tuning was immediately observable. Forty thousand people paid them to do their beta testing, and to co-develop the game with them. At every stage of the decision tree, thousands of fingers pointed out the green circles to them.

Leave aside the puny sample sizes of focus group studies/surveys, and try forty thousand people on for size. That many people did, not only their product development marketing, but also their advertising as well. I urge you to check out the Gamespot review for the game, and see the glaring disparity between the reviewer's rating and that of the gamers'.

Why do they love a game with graphics nowhere near AAA titles? Why a game that did not get marketed aggressively? Why a game that scores a shameful 6 on Gamespot's review? Simply because Mount&Blade did what the others could only dream of doing: it found the street address. And all that with a team of two people and a shoestring budget for absolutely everything.

Compared to the traditional video game marketing trip to Quebec, this approach is no different than having an onboard GPS system. The success of this humble indie title was no coincidence. It was, in fact, almost impossible for it to fail.

You may argue that the same design method cannot be applied to every situation for this reason or that. Just remember that while you are arguing that point, someone else out there may be just about to make it work for them.

And once that happens, imagine what a company that never misses can do.

1 comment:

Your blog is very interesting and insightful, even as a non-gamer and a non-business person. I wish you would continue!

Post a Comment